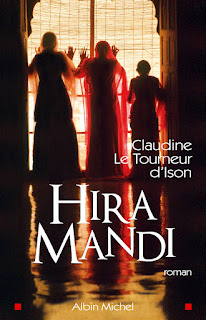

BOOK REVIEW: Hira Mandi / Author: Claudine Le Tourneur Dlson

Published in Daily Times Saturday, February 11, 2012

Reproduced on Claudine Le Tourneur Dlson's Website

Translated from French by Priyanka Jhijaria

Reviewed by Afrah Jamal

A programme about Hira Mandi did the internet rounds a couple of years ago. It claimed, among other things, that the sons of the ‘dancers’ reportedly end up as lawyers, doctors, artists — a few join politics and some even reach the military. These outrageous statistics may be one of the reasons the documentary was banned from the mainstream media. That and its primary premise — the plight of the fallen women — would prompt the conservatives to howl with dismay before scurrying off to bury any evidence in the backyard along with other bodies.

Claudine Le Tourneur d’Ison embeds such wrenching moments in a bold narrative where its doomed protagonist can hail the brave new world and its genteel patrons from an extraordinary vantage point. The expedition to the underworld with the unfortunate progeny and the hapless dwellers of ‘Hira Mandi’ (red-light district) that lasts six decades is both harrowing and unexpected. The wreckage of lost dreams decaying in the old walled city arrives on cue; happy endings leave by the same door in this new book generously seasoned with half a century’s worth of infamy.

Staged in the most infamous parts of Lahore, Hira Mandi turns this sensational premise with its overarching theme of misery into a lavish set piece where a young Shanwaz Nadeem enacts the story of Iqbal Hussain, a real life celebrity artist from Shahi Mohalla who proudly proclaims his controversial origins, choosing to portray the humane over the ugly. The same unapologetic streak runs throughout the novel. The main character is an exception to the rule, which declares the Shanwaz Nadeems of the world ineligible for greatness. In this reality, sons are a burden, left to wander the streets with pipedreams; daughters, however, are valued and brought up to inherit the ‘family business’.

Since the children from the red light district are easily picked out through their accents, the fate of its 10-year-old male protagonist appears sealed. Partition is on the horizon as the boy without a future is introduced as a “useless pawn on the chessboard of a marginal society”. As the offspring of a ‘dancer’, his coming of age runs parallel with a young nation. He will take on the role of an artist wielding art as a tool to extricate himself from his circumstances — and to claim a place in society for not just himself but also his ‘subjects’.

Readers must brace themselves for the depravity that goes with ‘Hira Mandi’ and the surprisingly devastating criticism that emanates from its icy foundations. The characters caught in Hira Mandi’s vice-like grip are framed against the fresh hopes of a fledgling nation set to embark on its maiden voyage. The novel is prompted by Shanwaz’s cynicism and disillusionment to confront the crooked dimensions of these parallel universes. Searing commentary mercilessly rips through the beautiful façade, leaving the memory of its most revered icons in shreds.

As a boy he listens to Pran Chowdhry — the friendly neighbourhood Hindu depicted as an ardent admirer of Gandhi, whose bias for the man responsible for partition cannot be concealed; Sikhs and Hindus are presented as the recipients of violence before they begin doling out their own brand of terror. In Pran’s eyes, Jinnah will appear as a “severe, unbending messiah” who terrorises his kind and walks with “a condescending smile on his bony face”. His sentiments are mirrored by an older Shanwaz who ruthlessly compares the hopes of pre-partition with the follies of the coming age in the same mocking tone that mournfully concludes that his “country never stopped paying for the savagery of its creation”.

The novel does not allow its tragic victims to stray very far. The ‘dancers’ become his muse, ‘Hira Mandi’ remains his stage, and fame beckons Shanwaz, however reluctantly. With these changes come some telling observations about “stiff, snobbish, self-centred society” now ready to fawn all over his work, the never ending political pantomimes and the ultimate fall of a nation to the “lowest degree of cultural destitution”. Some of the more traditional elements of this world will be swept away by the seismic shifts in its political/religious/social structure. He will be left to bemoan the original face of the district, then home to the rich and depraved and now frequented by the holier-than-thou, depraved politicians “who brandish the Book by day and lavish banknotes at night”. This ominous worldview succinctly defines the frustrations of his times and pauses to blame the British for the decline of the “great courtesan”. Here the past will be mercilessly dissected; the present viciously discarded, and a lost era quietly mourned from their lonely perch.

Shanwaz’s assessment of ‘Hira Mandi’, once home to royal courtesans, is kinder. He glides by aging dancers “entering the ghetto of other retired magicians, a desolate world of regrets and bitterness” prefacing their tragic lives with a befitting eulogy. Sometimes, a single beam of light can be enough to cut through centuries of murkiness and the boy who becomes the consciousness of a floundering nation carries the argument in favour of his ‘people’.

In a way Claudine Le Tourneur d’Ison is on the same quest as the protagonist — to give the death of these hopes and dreams a decent burial and jolt society out of its usual apathy. Hira Mandi’s greatest strength perhaps is the way it uses Pakistan’s moody political climate as an accomplice to provide a wider understanding of the history behind such places. Neither world can ever align and yet here they are — displayed side by side, the shifting sands of a modern republic and the medieval echoes of a stagnant soul.

Available at Liberty Books

Images Courtesy of: http://www.albin-michel.fr/multimedia/Article/Image/2006/9782226168214-j.jpg

Reproduced on Claudine Le Tourneur Dlson's Website

Translated from French by Priyanka Jhijaria

Reviewed by Afrah Jamal

A programme about Hira Mandi did the internet rounds a couple of years ago. It claimed, among other things, that the sons of the ‘dancers’ reportedly end up as lawyers, doctors, artists — a few join politics and some even reach the military. These outrageous statistics may be one of the reasons the documentary was banned from the mainstream media. That and its primary premise — the plight of the fallen women — would prompt the conservatives to howl with dismay before scurrying off to bury any evidence in the backyard along with other bodies.

Claudine Le Tourneur d’Ison embeds such wrenching moments in a bold narrative where its doomed protagonist can hail the brave new world and its genteel patrons from an extraordinary vantage point. The expedition to the underworld with the unfortunate progeny and the hapless dwellers of ‘Hira Mandi’ (red-light district) that lasts six decades is both harrowing and unexpected. The wreckage of lost dreams decaying in the old walled city arrives on cue; happy endings leave by the same door in this new book generously seasoned with half a century’s worth of infamy.

Staged in the most infamous parts of Lahore, Hira Mandi turns this sensational premise with its overarching theme of misery into a lavish set piece where a young Shanwaz Nadeem enacts the story of Iqbal Hussain, a real life celebrity artist from Shahi Mohalla who proudly proclaims his controversial origins, choosing to portray the humane over the ugly. The same unapologetic streak runs throughout the novel. The main character is an exception to the rule, which declares the Shanwaz Nadeems of the world ineligible for greatness. In this reality, sons are a burden, left to wander the streets with pipedreams; daughters, however, are valued and brought up to inherit the ‘family business’.

Since the children from the red light district are easily picked out through their accents, the fate of its 10-year-old male protagonist appears sealed. Partition is on the horizon as the boy without a future is introduced as a “useless pawn on the chessboard of a marginal society”. As the offspring of a ‘dancer’, his coming of age runs parallel with a young nation. He will take on the role of an artist wielding art as a tool to extricate himself from his circumstances — and to claim a place in society for not just himself but also his ‘subjects’.

Readers must brace themselves for the depravity that goes with ‘Hira Mandi’ and the surprisingly devastating criticism that emanates from its icy foundations. The characters caught in Hira Mandi’s vice-like grip are framed against the fresh hopes of a fledgling nation set to embark on its maiden voyage. The novel is prompted by Shanwaz’s cynicism and disillusionment to confront the crooked dimensions of these parallel universes. Searing commentary mercilessly rips through the beautiful façade, leaving the memory of its most revered icons in shreds.

As a boy he listens to Pran Chowdhry — the friendly neighbourhood Hindu depicted as an ardent admirer of Gandhi, whose bias for the man responsible for partition cannot be concealed; Sikhs and Hindus are presented as the recipients of violence before they begin doling out their own brand of terror. In Pran’s eyes, Jinnah will appear as a “severe, unbending messiah” who terrorises his kind and walks with “a condescending smile on his bony face”. His sentiments are mirrored by an older Shanwaz who ruthlessly compares the hopes of pre-partition with the follies of the coming age in the same mocking tone that mournfully concludes that his “country never stopped paying for the savagery of its creation”.

The novel does not allow its tragic victims to stray very far. The ‘dancers’ become his muse, ‘Hira Mandi’ remains his stage, and fame beckons Shanwaz, however reluctantly. With these changes come some telling observations about “stiff, snobbish, self-centred society” now ready to fawn all over his work, the never ending political pantomimes and the ultimate fall of a nation to the “lowest degree of cultural destitution”. Some of the more traditional elements of this world will be swept away by the seismic shifts in its political/religious/social structure. He will be left to bemoan the original face of the district, then home to the rich and depraved and now frequented by the holier-than-thou, depraved politicians “who brandish the Book by day and lavish banknotes at night”. This ominous worldview succinctly defines the frustrations of his times and pauses to blame the British for the decline of the “great courtesan”. Here the past will be mercilessly dissected; the present viciously discarded, and a lost era quietly mourned from their lonely perch.

Shanwaz’s assessment of ‘Hira Mandi’, once home to royal courtesans, is kinder. He glides by aging dancers “entering the ghetto of other retired magicians, a desolate world of regrets and bitterness” prefacing their tragic lives with a befitting eulogy. Sometimes, a single beam of light can be enough to cut through centuries of murkiness and the boy who becomes the consciousness of a floundering nation carries the argument in favour of his ‘people’.

In a way Claudine Le Tourneur d’Ison is on the same quest as the protagonist — to give the death of these hopes and dreams a decent burial and jolt society out of its usual apathy. Hira Mandi’s greatest strength perhaps is the way it uses Pakistan’s moody political climate as an accomplice to provide a wider understanding of the history behind such places. Neither world can ever align and yet here they are — displayed side by side, the shifting sands of a modern republic and the medieval echoes of a stagnant soul.

Available at Liberty Books

Images Courtesy of: http://www.albin-michel.fr/multimedia/Article/Image/2006/9782226168214-j.jpg

Comments

Post a Comment