VIEW: Coups: Bloody, Medium, Rare

Published in Daily Times / Saturday, January 14, 2012

By Afrah Jamal

One cannot initiate a change of guard in Pakistan without sending the entire nation into a paroxysm or rattling the international community. Not when said change comes atop a war of (some very mean sounding) words between the state and its military.

The New York Times (NYT) editorial, ‘Pakistan’s besieged government’ (January 12, 2012) appears concerned about the fate of Pakistan’s democracy. They hint at “disastrous patterns” and bring up the olden days, implying that a repeat of those times is perhaps in the offing. They then observe that “no civilian government in Pakistan has ever finished its term” and hope that this one would be allowed to do so. Their concern is touching.

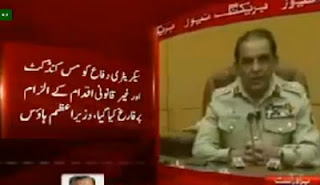

The latest crisis precipitated by the firing of the Defence Secretary and the prime minister’s ill-timed statements against our omnipotent military commanders triggered warning bells for Pakistan’s fledging democracy. These back to back incidents gave the impression that a coup was imminent, leading to frenzied speculations. Those who tuned in to the media (mainstream, social) came upon stricken-looking anchors, hysterical headlines and hurried debates all centred on a possible military takeover. These fears are not entirely unfounded and emerge from a not-so-distant past where the military, skilled in overnight redecoration, dictated the national narrative. The bitter aftertaste of earlier coups continues to linger.

Recent events show the military to be in tune with the public sentiments — however grudgingly, not because their special brand of coups (bloody-medium-rare) are no longer effective but maybe because there is less tolerance and sweeter alternatives available. Nevertheless, a coup is the first thing that comes to mind (theirs, ours, everyone’s) when the judiciary, military and the government start exchanging pleasantries and tacking words like dishonest, treacherous, violator of the constitution to the postscripts. Sternly worded warnings issued by the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) countering the prime minister’s accusations can only fuel our overactive imaginations.

The landscape has changed drastically over the past 10 years and yet something remains the same. Pakistan is used to waking up in the morning to fresh faces and a shiny new leadership. The people clamour for a military takeover and then resent them for it. Each time the situation warrants an intervention. Each time it ends badly. Yes, the public is fickle — their taste in politicians is questionable, their memory is notoriously short and choices are limited. But their stance on military rule has always been clear.

Coups, even if they appear justified at the time, are to be discouraged for several reasons. Governments that cannot finish their tenure then accuse the establishment of cramping their style and use these pleas to garner sympathy for their next bid. And it works. Political martyrdom allows the same faces to keep coming back, citing these interruptions as the sole reason for their spectacular failures.

While a coup may not be forthcoming, some changes might. Political parties seem geared up to bid adieu to the government. Something has set events in motion, which might lead the Opposition to seek a no-confidence vote in parliament (the PML-N reportedly falls short of the required votes) or convince either Imran Khan to start his civil disobedience movement or the government to agree to a fall election.

Pakistan’s young democracy needs to find a foothold. The present government has had a busy four years — they have fallen out with the judiciary, the military and the people and quietly watched the railways, airlines and steel mills implode. If people are disillusioned it is not just because the leaders failed to deliver on those enticing promises but because they appeared indifferent to the current tailspin.

No one disagrees with the NYT’s airy observations that “no civilian will ever be able to do a competent job if the military keeps pulling the strings”. The military men have had ample opportunities to step in but they have spent the better part of 2011 quashing such rumours. The danger seems to have been averted but that ‘endangered’ sign continues to hang outside the civilian government’s doorstep. This government is in a legal bind, some might argue of its own making. Others will find it ironic that trying to safeguard their government against an imaginary coup actually brought them to the brink of a real one.

Images Courtesy of: http://www.newageislam.com/controlpanel/picture_library/bohan114.jpg

http://videos.onepakistan.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/news-beat2.jpg

http://www.jagodunya.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/javed_hashmi-imran-khan-nawaz-sharif-pti-jagodunya.jpg

By Afrah Jamal

One cannot initiate a change of guard in Pakistan without sending the entire nation into a paroxysm or rattling the international community. Not when said change comes atop a war of (some very mean sounding) words between the state and its military.

The New York Times (NYT) editorial, ‘Pakistan’s besieged government’ (January 12, 2012) appears concerned about the fate of Pakistan’s democracy. They hint at “disastrous patterns” and bring up the olden days, implying that a repeat of those times is perhaps in the offing. They then observe that “no civilian government in Pakistan has ever finished its term” and hope that this one would be allowed to do so. Their concern is touching.

The latest crisis precipitated by the firing of the Defence Secretary and the prime minister’s ill-timed statements against our omnipotent military commanders triggered warning bells for Pakistan’s fledging democracy. These back to back incidents gave the impression that a coup was imminent, leading to frenzied speculations. Those who tuned in to the media (mainstream, social) came upon stricken-looking anchors, hysterical headlines and hurried debates all centred on a possible military takeover. These fears are not entirely unfounded and emerge from a not-so-distant past where the military, skilled in overnight redecoration, dictated the national narrative. The bitter aftertaste of earlier coups continues to linger.

Recent events show the military to be in tune with the public sentiments — however grudgingly, not because their special brand of coups (bloody-medium-rare) are no longer effective but maybe because there is less tolerance and sweeter alternatives available. Nevertheless, a coup is the first thing that comes to mind (theirs, ours, everyone’s) when the judiciary, military and the government start exchanging pleasantries and tacking words like dishonest, treacherous, violator of the constitution to the postscripts. Sternly worded warnings issued by the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) countering the prime minister’s accusations can only fuel our overactive imaginations.

The landscape has changed drastically over the past 10 years and yet something remains the same. Pakistan is used to waking up in the morning to fresh faces and a shiny new leadership. The people clamour for a military takeover and then resent them for it. Each time the situation warrants an intervention. Each time it ends badly. Yes, the public is fickle — their taste in politicians is questionable, their memory is notoriously short and choices are limited. But their stance on military rule has always been clear.

Coups, even if they appear justified at the time, are to be discouraged for several reasons. Governments that cannot finish their tenure then accuse the establishment of cramping their style and use these pleas to garner sympathy for their next bid. And it works. Political martyrdom allows the same faces to keep coming back, citing these interruptions as the sole reason for their spectacular failures.

While a coup may not be forthcoming, some changes might. Political parties seem geared up to bid adieu to the government. Something has set events in motion, which might lead the Opposition to seek a no-confidence vote in parliament (the PML-N reportedly falls short of the required votes) or convince either Imran Khan to start his civil disobedience movement or the government to agree to a fall election.

Pakistan’s young democracy needs to find a foothold. The present government has had a busy four years — they have fallen out with the judiciary, the military and the people and quietly watched the railways, airlines and steel mills implode. If people are disillusioned it is not just because the leaders failed to deliver on those enticing promises but because they appeared indifferent to the current tailspin.

No one disagrees with the NYT’s airy observations that “no civilian will ever be able to do a competent job if the military keeps pulling the strings”. The military men have had ample opportunities to step in but they have spent the better part of 2011 quashing such rumours. The danger seems to have been averted but that ‘endangered’ sign continues to hang outside the civilian government’s doorstep. This government is in a legal bind, some might argue of its own making. Others will find it ironic that trying to safeguard their government against an imaginary coup actually brought them to the brink of a real one.

Images Courtesy of: http://www.newageislam.com/controlpanel/picture_library/bohan114.jpg

http://videos.onepakistan.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/news-beat2.jpg

http://www.jagodunya.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/javed_hashmi-imran-khan-nawaz-sharif-pti-jagodunya.jpg

Comments

Post a Comment